The Elevation of Craft from Folk to Art: Mingei, Minka, and Preservation in Modern Japan

By Taylor Bond

Imagine art intended for everyday use, not destined to be barricaded behind gilded frames and glass museum cases. Picture the edges of clay cups made smooth by skin, softened by the daily devotion of being passed around the hands of a happy family, functioning as the centerpiece of shared meals. Or, the curved neck of a teapot, produced to serve in both the pageantry of tea ceremonies and the humble stage of a local home. Objects designed for the ordinary people. Painstakingly created by artisans and unknown craftsmen to be well-used and well-loved, instead of merely admired from a distance.

Occasionally, these craft creations can even be lived in, such as the case of minka homes, lauded for their simplicity and craftsmanship. While the homes may be humble, they have come to be appreciated specifically for their modest vitality. This belief, the magic contained in the commonplace, is what served as a catalyst for the mingei folk craft movement in Japan, and what continues to drive the momentum of preserving craft today. While these objects have always been appreciated by those who use them, they weren’t recognized as art in an official capacity until the efforts of one aesthete began to spread.

The Birth of the Mingei Movement

Within Japan, the mingei folk art movement was spearheaded by Soetsu Yanagi, a philosopher, an essayist, a scholar of Zen and tea, and a man altogether wholly devoted to a life in pursuit of aesthetics and beauty. Born in 1889 during a time of undeniable cultural influx, Yanagi witnessed the wave of Westernization crash upon the shores of Meiji Japan, and the struggle Japan faced to define itself as a modern nation-state, both internally and externally. Modernization arrived rapidly, migration from rural villages to bustling cities started, and the previous cornerstones of life were uprooted in this whirlwind of change. It was in this environment, steeped in frantic upheaval and advancement, that Yanagi sought out the straightforward purity provided by the folk craft aesthetic. Greatly inspired by the pottery of the Korean kingdom, as well as by the Arts and Crafts movement occurring in Britain at that time, Yanagi soon turned to his home country of Japan for inspiration and implementation of his ideas about art and true beauty.

To Yanagi, the beauty of folk crafts was multi-faceted. His ideal works were made from nature, crafted by hand, both upholding tradition and designed with simplicity in mind. Functionality in form was prioritized over extraneous detail, with an emphasis on easy replicability. Folk art was not designed to be singular, hoarded away in a collection and admired only from a distance, but rather a craft to be shared with the community—more specifically, at an affordable cost that encouraged accessibility for all. These were artworks designed by the common people, for the common people, and included a myriad of final products, including lanterns, tea kettles, toys, fans, pottery, and other items of everyday use.

The divide between fine art and folk art is one often believed to be stark and insurmountable. Some say that true art only exists in the extremes—of lavishness, refinement, or style signifying status; however, others disagree and find beauty in the humble, honest craft art that esteems usefulness above all else. After all, who can claim that the beauty held within a Monet or Picasso, a Hokusai or a Sesshu, surpasses the charm contained in the hand-stitched futon-gawa quilt cover that has cradled the children of a community, generation after generation? The warmth retained within the everyday object is poignant with its subdued style and ability to serve a genuine purpose. As a whole, folk art is a discipline where every facet of the final masterpiece is focused on functionality, where the preciousness of the item is built off of practicality.

Yanagi’s views on the cultivation of art aligned closely with the Zen concept of mushin, or “no-mind,” in which emotions or thoughts are dropped, allowing the mind to be open to fully perceive its surroundings. He stressed the need to develop the habit of looking without judging, passively receiving the world’s experiences without staining it with the self. For Yanagi, recognizing art in the world was an intuitive reflex, and he believed that in witnessing pure, universal beauty, humans could find spiritual harmony within themselves. He saw the artisanal elegance in the objects that surrounded him in daily life, and in that, a greater appreciation for the world as a whole. Soon, others followed in his mindset of seeking beauty in the common things and considering craft products that could be found in local houses on the same level as fine art sheltered in private collections.

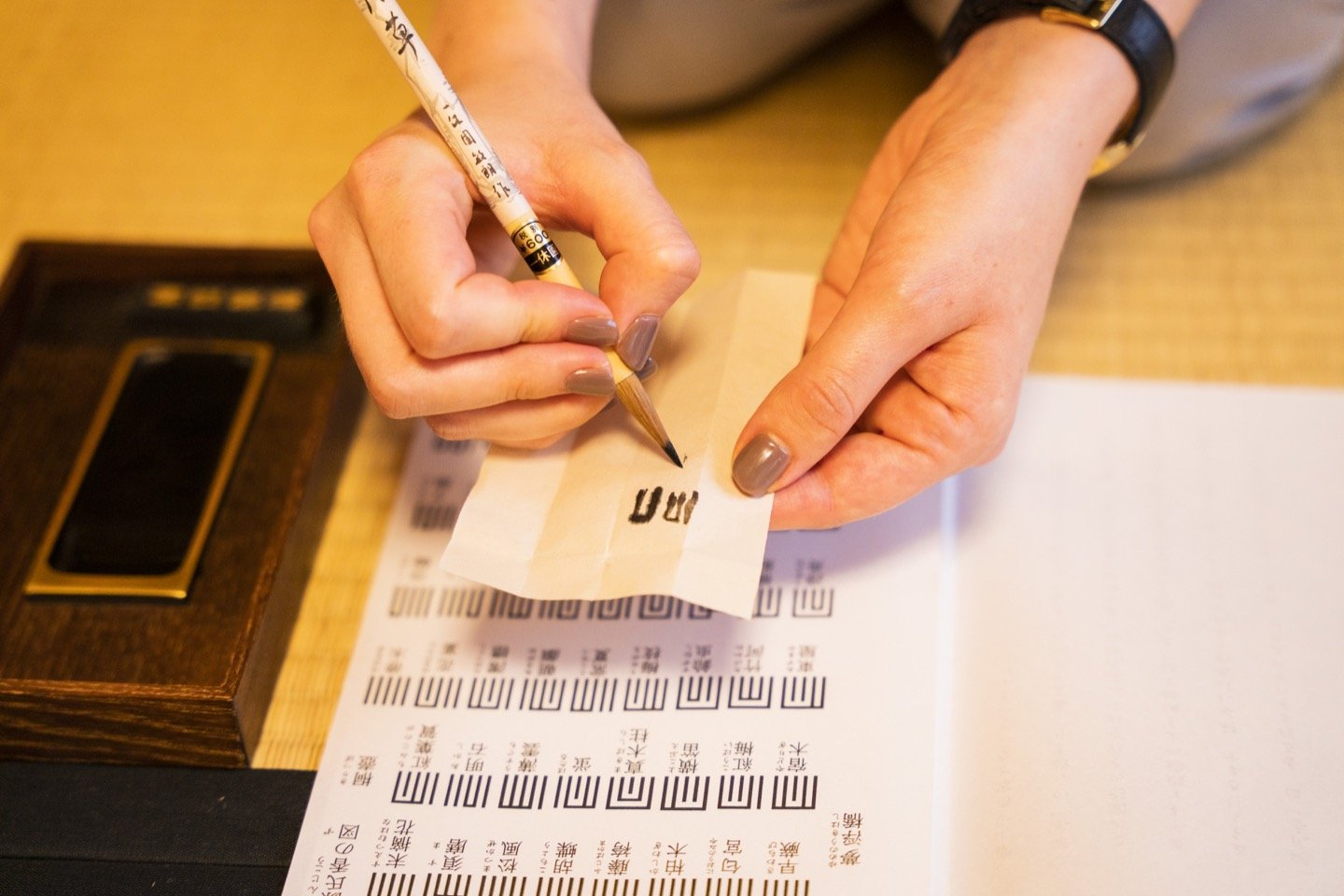

Modern Japan still retains the reverence for craft that Yanagi valued. While mingei as a discipline overall deemphasizes the role of the artisan, focusing instead on the objects’ everyday usage, contemporary commentators place value on both the craft and the craftsperson. Master makers in a range of disciplines continue to dedicate their lives to honing specialized skills and creating hand-made objects. And while the number of these artisans has certainly decreased with time, a proud few still remain devoted to fostering the preservation of these crafts for generations to come. Day after day, they embrace art into the everyday, contributing to fields of creation such as lacquerware, metalwork, dyed cloth, and countless other different creative mediums. And, within all of their final products, a tangible sense of expertise and aesthetic insight can be clearly seen.

Minka and Living in Craft Culture

This concept of beauty enhanced by the everyday is not merely limited to objects but is also deeply embedded into the very structure surrounding daily life. Minka, translated directly as the “people’s house,” are traditional Japanese dwellings historically used by the non-samurai castes of society. The layout and construction of these houses vary by region, but what remains constant is the customization accounting for local climate and utilization of locally sourced materials. Each home is designed to suit its surroundings, seamlessly interweaving available supplies into the construction of each home—areas with abundant bamboo utilized the material for roofs and floors, locations lacking reeds for thatched roofs used shingles instead, and even houses constructed in volcanic areas infused volcanic rock into their structure.

Multiple clusters of minka homes throughout Japan have been designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, most notably those in Gokayama and Shirakawa-go. The sweeping wooden structures and austere thatched roof style of the houses have been painstakingly preserved throughout history. And, it continues to convey an undeniable sense of beauty to even modern audiences, with visitors flocking to observe the unique architecture and even nestling in for a night or two for a minka homestay experience.

Like the mingei craft art movement, minka fascinates with its emphasis on utility, preservation of tradition, and understated yet ever-present beauty. Also similarly to the field of folk art, there are questions about how to best maintain this tradition in a modern setting. After all, as technology continues to advance and society pushes toward the future, retaining these traditions becomes less of a given outcome, and more of a conscious decision. In a world where so many products and designs are mass-produced, building things from hand with local materials is not as common as it once was.

While many contemporary construction companies and architects no longer consider minka when erecting present-day homes or housing developments, there are groups of devoted disciples who still remain single-mindedly dedicated to the maintenance and conservation of these folk houses. Followers gather annually at the Minka Summit, which is composed of various panels discussing preservation techniques, interactive workshops, and guest speakers lecturing on the minka aesthetic. Their intense admiration helps sustain the use of minka in everyday settings, continuing the style for future generations to come. Even more, there’s a growing demand for minka not only within Japan’s domestic market but also outwards as well, with original minka structures exported as far as England and Argentina. Clearly, something about the subtle beauty ingrained in minka homes resonates with an increasingly diverse audience, unbound by borders, and will help to propel the preservation of the minka lifestyle for years to come.

Minka and Mingei in a Modern Context

Both mingei and minka continue to withstand the tests of time. The conscious maintenance of these two fields of folk art and living are by no means the only examples of tradition remaining essential to, or revered by, modern citizens. On an institutional level, Japan has enacted a multitude of programs to support the continuation of these crafts, including designating master craftsmen as Living National Treasures, safeguarding certain Intangible Cultural Heritage crafts, and providing financial assistance to artisans.

Like a small flame tended to by loving hands, folk crafts continue to grow, dynamic and alive, in various pockets throughout the country. And while some aspects of the art remain staunchly the same, other implementations of craft have evolved with the changing times. Homes that once housed Edo merchants are transformed into the structures for trendy cafes, the hues decorating iron tea kettles have expanded to suit vibrant modern tastes, and new vitality is breathed into these old styles of craft.

In this way, the art of the everyday can continue to be seen, appreciated, and admired. For now, and for countless future generations to come.

About the Author: A creative writer and Japanese Literature and Culture scholar, Taylor Bond focuses her academic research on cultural formation, folklore, and East Asian comparative culture. Her creative work includes both prose and poetic content, often exploring themes of the self and lyrical surrealism.