Classical Words, Contemporary Feel: Development of the Japanese Waka Poem

By Genie Harrison

Longing for you,

loving you,

waiting for you,

the bamboo blinds were swayed

only by the autumn wind.

Princess Nukada (7th Century), translated by Kenneth Rexroth

One of the greatest poets of the Asuka period (538-710 CE), Princess Nukada was renowned for her ability to delicately parallel the movements and feeling of the natural world with the sentiments of her heart. In this poem, she declares both the longevity and quiet stoicism of her love: invoking an autumnal breeze, she gestures towards her staid composure against a backdrop of seasonal change. She figures in the world of Eastern classical literature as something of a fabled figure; ‘half-legendary,’ she was considered to be a divine messenger, oracle as well as a public poet. Thirteen of her poems feature in the Man’yoshu, the oldest extant collection of waka poetry, making her one of the most prominently featured writers in the work.

Literally meaning “Japanese poem,” the waka style of poetry came to be during the Nara (710-784) and early Heian Period (794-1185) in Japan. The oldest surviving anthology of waka known as the Man’yoshu comprises 20-volumes and over 4,500 individual lyrics. While the term waka originally encompassed a number of variations on the theme (tanka, chouka, sedoka), today it generally refers to the tanka, or “short poem.” Drawing on ancient Chinese poetic models, waka is determined by its syllabic structure and 5-7-5-7-7 meter, and it is the foundation upon which the modern haiku (5-7-5 meter) is based.

The Dark Age

Thoughts of a thousand things

fill me with melancholy

as I gaze upon the moon,

but autumn’s dejection comes

not to me alone.

Oe no Chisato (9th Century), translated by Peter McMillan

Prior to the codification of waka in the 9th and 10th centuries, Japanese literature underwent what is now referred to as its “dark age.” Poets of this period wrote exclusively in classical Chinese, fervently believing in the value of using a language not only ascribed prestige but, moreover, read throughout the known world – China and Korea.

On nineteen occasions during the years 630 to 894, the Japanese court had sent official envoys to China, at that point under the control of the Tang Empire (618-907). The aim of these missions was to enable the Japanese court to assimilate elements of Tang civilization into Japanese society–government processes, economics, and culture. The Chinese literary and linguistic tradition was esteemed to such an extent that the very existence of writing in the Japanese language was threatened. However, as the Tang dynasty began to decline, so too did the relevance and value of these missions, which were incredibly arduous and often fatal. The last official envoy was sent from Japan to China in 834.

As a result of the severance with China, the members of the ancient Japanese courts were now pushed to look inward for cultural inspiration: the development of stylistic practices and talent would have to be borne domestically.

Soon after, in 894, Emperor Uda commanded the poet Oe no Chisato to compile a collection of waka poetry. Chisato compiled a collection of 110 waka poems, each composed by taking one line from a Chinese poem and remolding it into the burgeoning waka style. The anthology was aptly titled Kudai Waka (“Waka on Theme of Lines”). This recognition of waka on the nation’s highest level signaled the resurgence of poetry in the Japanese language – and with it, the end of this poetic “dark age.”

Style and Uses of Waka Poetry: The Courts of Japan

The orange tree

we planted in my garden

as a symbol of our love,

though we have come to regret it, our love

was worth doing.

Otomo no Sakanoe no Iratsume (8th Century), translated by Kenneth Rexroth

With its imperial approval and resulting growth in popularity, waka poetry became intrinsic to the world of the court, developing a ceremonial function. Highly formal court parties would often culminate in what might today be referred to as “poetry contests,” during which Japanese aristocracy competed to produce highly skilled renditions of the art through chanting – and even singing.

Emerging in conversation with these elite gatherings, the waka soon became synonymous with the aristocratic practice of Incense Ceremony, or kodo. In this court tradition, waka poetry was paired with specific notes of fragrance within the incense. While the ceremony is being conducted, participants “listen” to the aromas chosen by the ceremony master, and waka poems, carefully selected to enhance the experience of each fragrance, are read alongside. While different schools engaged in this fusion of scent and poetry, it is a practice that has come to be particularly associated with the Shino School of Kodo. Even today, waka poems are read and used during incense ceremonies, with the poetry chanted in patterns similar to those of a Gregorian chant.

Style and Uses of Waka Poetry: The Private Sphere

Although it was the Japanese court’s deep-rooted love for waka that cemented the art form as an essential aspect of Japanese culture, the literature also found its way into the everyday lives of common folk. The content covered in the waka poems was dynamic and varied, ranging from victory in battle and expressions of piety to declarations of love and the changing of the seasons. The ability to compose a waka poem on any given topic became an essential skill, requiring masterful ingenuity and a wealth of topical knowledge.

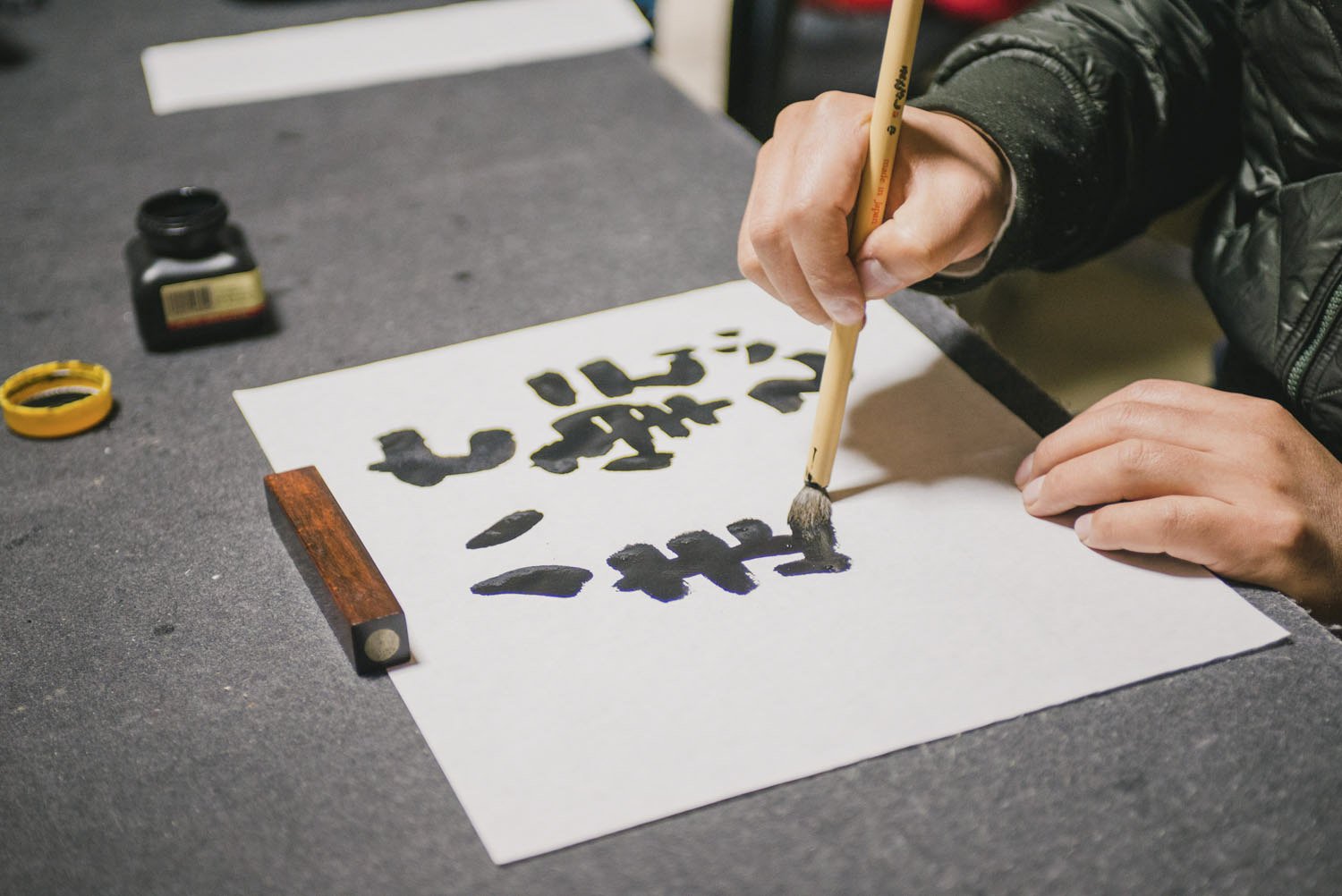

In the private domain, waka became a useful shorthand for communication between friends and lovers. Expanding beyond the scope of merely the literary, waka came to be used in a far more intimate and personal way than the traditional Chinese poetry from which it had developed. Indeed, the ideal suitor was known ‘for his elegance and his ability to compose a well-turned poem’––all the while obeying the rules of ‘good taste.’ Success in love was predicated on not only the technical skill of these poems – the words of the waka – but moreover on the exquisiteness of their poetic presentation. The calligraphic skill with which these poems were rendered was critical to successful marital bids, and it was commonplace for adolescent girls to spend hours painstakingly perfecting these techniques to promote their chances of favorable matrimony.

Women and Waka

I fell asleep thinking of him,

and he came to me.

If I had known it was only a dream

I would never have awakened.

Ono no Komachi (9th Century), translated by Kenneth Rexroth

At the same time that Japanese literature saw its renaissance through waka, the newly devised writing system of hiragana was growing in popularity across the country.

While the male population at the time preferred to use kanji (Chinese characters), women quickly adopted the new script, due to its direct correspondence to the spoken sounds of Japanese. ‘Swift-moving and graceful in its shapes,’ hiragana was well-matched not only to the needs of the Heian court ladies but to the common people as well, affording women an unprecedented access into the literary world. Especially given its suitability to calligraphy, it provided the necessary foundation for a great age of women writers.

One such writer is Ono no Komachi. One of the most well-respected waka poets of the early Heian period, Komachi wrote poems spanning themes of love, loss, solitude, and eroticism. Very little is known about Ono no Komachi’s family ties, with sources suggesting her to have been born outside of the realm of the court. Although it was not uncommon for women from non-aristocratic backgrounds to compose personal and even religious waka, it was the arrival of hiragana which allowed those poems to endure.

In 905, Komachi’s words were included in a new imperial anthology of poetry known as the Kokin Wakashu. The Kokin Wakashu was particularly significant because it surveyed all of Japanese poetry, including not only kanji but hiragana, as well. As American-Japanese historian Donald Keene saw it, ‘the literature in Japanese of the Heian period could not have existed without the two kana syllabaries.’

With the Kokin Wakashu’s popularity enduring even to this day, it is clear the role women of the Heian Period – and the introduction of hiragana – played in the development of waka and the greater tradition of Japanese literature.

The Path of Waka: In the Past and in the Present

A deeper understanding of waka’s range of developments and stylistic variations allow for a more fully-fledged understanding of its primary impulse: ‘to express what lay in the poet’s heart.’ On account of its concise form, waka is limited in its ability to tell the sprawling, epic tales that were commonplace in Western literature at the time. However, the brevity of words used did not compromise the depth of the meaning imparted, nor did strictly adhering to the style’s tell-tale structure limit creative freedom. In fact, it is directly in the formal waka structure that the deep emotion of poets like Princess Nukada, Chisato, Iratsume, and Komachi is realized. Giving oneself over to the limits of the poetic form, the task of the contemporary waka enthusiast is the very same as that of the waka poet writing in antiquity – to carefully distill into a number of mere syllables, what lies dormant within the heart.

About the Author: A recipient of the Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Scholarship, Genie Harrison is a writer currently based in Tokyo, where she works for popular lifestyle magazine, Tokyo Weekender. Educated at the University of Cambridge, she specializes in literature, with a particular focus on contemporary fiction written by Japanese female authors.