Unsheathing Bushido and Gender: The Female Samurai Warriors of Aizu

By Tamaki Hoshi

Amidst the chaos of the battlefield, Takeko Nakano and her comrades charged forward with determination etched on their faces. Their hair, once flowing, was now freshly shorn. Instead of the katana swords wielded by male samurai warriors, these female fighters held naginata long swords 薙刀 with an unwavering grip, dauntlessly facing the incoming troops. Known as the joshitai 娘子隊, this spontaneously organized group of women warriors from the Aizu domain fought fiercely against the Imperial forces during the Boshin War (1868-1869). Despite this sincere and courageous act, the joshitai were ultimately unsuccessful, and the win by the Imperial forces not only cemented the downfall of the Tokugawa Shogunate but also the abolition of the samurai social class. Yet even today, the story of Takeko and her peers has lasting implications for our understanding of the conventional gender expectations of feudal Japan, as well as the traditional samurai code of honor known as bushido.

Indeed, the prevailing contemporary notion portrays women of elite samurai lineage as reserved, domesticated figures, gracefully navigating their heavy silk kimonos as they tended to household duties. This assumption is - in part - true, but raises a contradiction: How could these “domesticated” women suddenly pick up their naginata and fearlessly enter battle? And, what truly defines bushido, the so-called way of the warrior? By unraveling the stories and the brave actions of Aizu's female warriors, and by delving into their noble death poems which revered life, a deeper understanding of "bushido" can be witnessed - one that transcends gender lines and challenges the misconceptions held even today of the true samurai code of living.

What is Bushido?

Bushido or “the way of the warrior” refers to a certain code of ethics or spirituality practiced among the samurai and is often considered one of the “Five Fountainheads of Japanese Philosophy.” While it alludes to stories of pre-modern samurai warriors, the term itself was coined in the Meiji Era (1868 - 1912) upon the elimination of the samurai class and the opening of Japan's borders at the conclusion of the Boshin War. Bushido then developed as a discursive mechanism to define a “Japanese spirit” against the rapid influx of Western ideology and ideas of “chivalry” and “gentlemanship.” Within such discourse, bushido became inevitably associated with masculinity, resulting in the hyper-masculine image of samurai that endures to this day.

Extending off those misconceptions of masculinity, the way of the warrior .became linked with a philosophy of death often expressed through the act of "seppuku" 切腹, the ritualistic suicide through disembowelment. In practice, however, bushidō primarily emphasized virtues like chugi (忠義) or “loyalty,” yuki (勇気) or “courage,” makoto (誠) or “sincerity,” and jin (仁) or “benevolence.” The deliberate choice to put one’s life on the line for a purpose served as a measure of the extent of a samurai’s loyalty, courage, and sincerity. It was these virtues of bushido - not a blind, fervent lust for death and battle - that became the driving force behind the way of the warrior.

Bushido, Death Poems, and Daily Life

On August 21, 1868, the Imperial army breached the Aizu border, marking the beginning of the Battle of Aizu of the Boshin War. Two days later, they launched their invasion of the Aizu Castle. Amid heavy rain, Takeko Nakano arrived at battle ready to meet her fate, bearing not just a naginata, but also a jisei 辞世, or “death poem,” a poignant reminder of mortality. She tied her writing to her weapon, its words echoing the courage of those who would fight alongside her:

I would not dare to count myself

among all the famous warriors

– even though I share the same brave heart.

–Nakano Takeko

Death poems, serving as farewell messages, were thought to embody the essence of the writer. The custom of writing death poems was particularly widespread among samurai warriors who faced perpetual peril, reflecting their perspective on life in the face of imminent death. Indeed, even for the most well-cited samurai within the discourse on bushido, death as a price for loyalty was something accepted with a heavy—though unwavering—heart.

One such example is the renowned story of Taira no Tadanori (平忠度) in the Tale of Heike ( ≈1330), in which he sorrowfully writes the following death poem and ties it to his bow as he heads off to a losing battle:

Overtaken by darkness,

I will lodge under a cherry tree’s branches;

flowers alone will bower me tonight.

–Taira no Tadanori

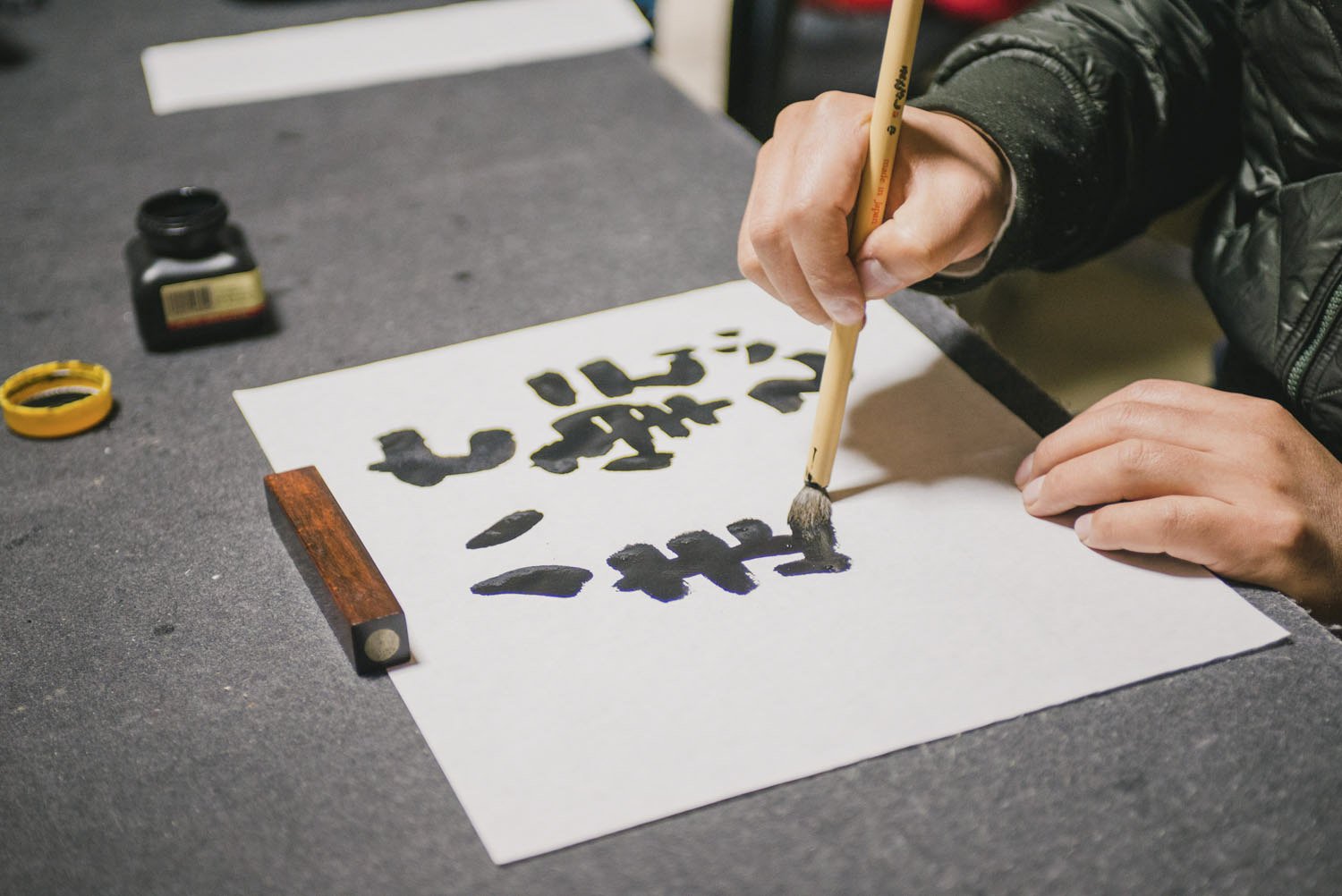

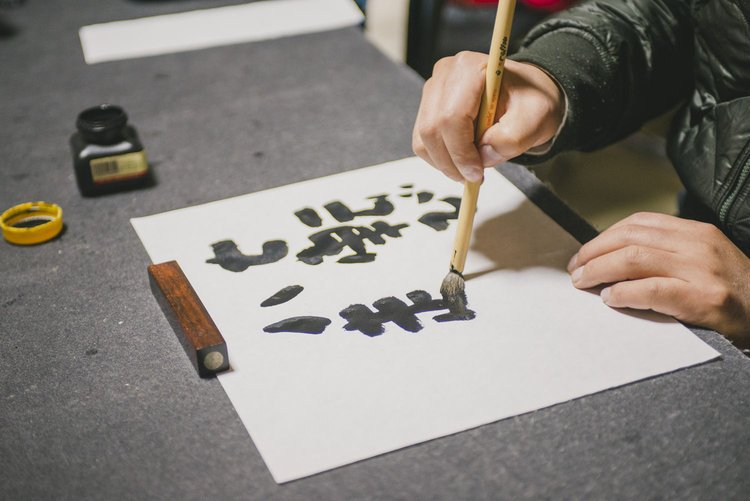

The spiritual tranquility of Tadanori as he approached his final moments, and his ability to calmly lay bare his sincerity through calligraphy amid the ferocity of battle, has long existed in Japanese collective memory as a symbolic representation of bushido. A comparable tone of dignified melancholy is echoed in Nakano Takeko's death poem, penned nearly seven centuries later. While neither a man nor a martially trained samurai warrior, Takeko’s story remains a testament to her loyal, courageous, and sincere character. Like Tadanori, Takeko embodies the "same brave heart" of samurai warriors, the brave heart from which the essence of bushido truly stems.

As demonstrated by the complexity of death poems, bushido cannot be reduced to a mere “philosophy of death” or a set martial code. Stories of warriors like Taira no Tadanori expressing sincere emotions suggest that the essence of bushido maintains a profound connection to how one perceives and approaches life. In this, one can see how bushido abides not by a “philosophy of death” but rather by a “philosophy of life.”

As Nitobe Inazo outlined in his Bushido: The Soul of Japan (1900), one who practices the ways of bushido must do so in the way they observe “their daily life as well as (...) their vocation.” With this mentality, bushido encompasses principles far more nuanced than the sentiment of simply seeking death as popularized in contemporary depictions of the way of the warrior. It is more aptly a code practiced not just on the battlefield, but through all of life’s everyday moments. And, while primarily associated with male warriors and their shared understanding of manners and morality, its underlying philosophy of loyalty, benevolence, sincerity, and courage could be similarly seen in the traditional domain of women: loyalty to the household, benevolence in nurturing the young and elderly, sincerity in their words and actions, and courage in their resignation to give up anything for the propensity and honor of their clan.

Female Warriors in the Battle of Aizu

Upon hearing of the Imperial Army’s invasion of the Aizu domain, over twenty women joined Takeko to voluntarily form the joshitai. These women chose to step out onto the battlefield to protect Princess Teru to whom they had pledged their allegiance. Despite lacking the same martial training as their male counterparts, the women had been taught to use the naginata for self-defense, a standard practice in the Aizu domain. However, focusing solely on their martial skills risks oversimplifying the issue, reducing their abilities to a matter of sheer practicality and bushido to merely a fighting spirit. Beyond taking part in direct combat, these women contributed to the battle in other ways, further embodying “the way of the warrior” through their selfless actions.

In his recollections of the invasion of Aizu’s castle, a young Aizu warrior named Kajinosuke Ibuka recounts how a woman had urged him to eat when he had lost his appetite and will to keep fighting. Amid the flying bullets and burning castle, the women in the castle continued to treat the wounded and feed the soldiers. Becoming a strong constant amid the chaos was not a simple task. Niijima Yaeko recounts how the palms of her hands were blistered and burned from having to hastily make rice balls straight out of the pot. Another intriguing account reveals how the women who chose to stay at the castle and take care of the wounded peeled the tatami mats from the castle floors and moved them outside for protection and bedding. While tatami floor mats proved a tactical advantage for both their lightness and their durability, it was the wit of these women, as domestic managers who deeply understood the makings of their houses, that allowed for such efficient strategizing.

Although Takeko and her comrades ultimately died in the Battle of Aizu, their story exemplifies the virtues of bushido: loyalty, courage, sincerity, and benevolence. These accounts of the battle demonstrate how the women of the Aizu domain embodied the unflinching “brave heart” of warriors past, not only through physical combat but also through nurturing an inner sense of duty and benevolence, assisting as caretakers who calmly treated the injured, fed soldiers amid the battle, and above all, served the clan with fearlessness and nobility.

In understanding bushido as a practice impacting all aspects of life irrespective of gender lines, we can see how its virtues extend beyond the typical masculine caricature of the samurai warrior and encompass a much broader range of loyalty and ethics – a code similarly instilled deep within the joshitai. Indeed, it was these shared virtues and a deeply felt “philosophy of life” that allowed the women of Aizu to pick up their naginata during the Boshin War.

While modern conceptions of bushido may stem from a gendered interpretation of life in feudal Japan, the underlying essence of bushido, in practice, was something unbounded by gender roles. Indeed, in a society that conceptualized household honor as something worth dying for, the role of household manager undoubtedly held great significance and weight, allowing these women to internalize their honorable identity and develop their inner bushido. As demonstrated by the samurai women of Aizu, we are reminded that even the simplest of tasks, like kneading rice balls or caring for our homes, becomes an opportunity to nurture our inner strength. As we navigate the complexities of modern life, let us reflect on what it truly means to have a brave heart like Takeko and her comrades, drawing strength from the virtues of bushido to face each day with burning resilience and compassionate grace.

About the Author: Tamaki Hoshi is a scholar and aspiring novelist with a passion for both Japanese women's history and intellectual history. She is currently researching the effects of modernization on Japanese women and the collective memory of motherhood in prewar and wartime Japan at Waseda University. Through her research and writing, she strives to illuminate the untold stories of women in Japanese history.

Dive into these experiences

星亮一.「女たちの会津戦争」(平凡社新書,2006)

新渡戸 稲造(著)、奈良本 辰也(訳)、新渡戸稲造博士と武士道に学ぶ会(編集). 「武士道:ビジュアル版 対訳 」(三笠書房, 2016).

中村彰彦.「会津武士道」(PHP文庫,2012).

新渡戸 稲造(著)、奈良本 辰也(訳)、新渡戸稲造博士と武士道に学ぶ会(編集).

「武士道:ビジュアル版 対訳 」(三笠書房, 2016).

Kasulis, Thomas. "Japanese Philosophy." In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Winter 2022 Edition, edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman. URL: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2022/entries/japanese-philosophy/.

Benesch, Oleg. Inventing the Way of the Samurai: Nationalism, Internationalism, and Bushidō in Modern Japan. Oxford University Press, 2014.